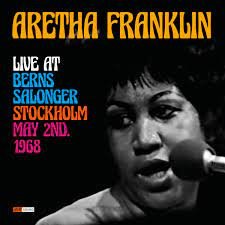

Aretha Franklin Live at Berns Salonger, Stockholm May 2nd, 1968 reviewed by Jeromiah Taylor

Aretha Franklin’s fear of flying was well known, and often used as an explanation for her dearth of overseas public engagements. Her phobia was the result of a particularly turbulent plane ride in 1984, prior to which she’d flown all over the globe. The latest release from Franklin’s estate, Aretha Franklin Live at Berns Salonger, Stockholm May 2nd, 1968, attests to the good fortune enjoyed by those able to see Franklin before she limited her travel. Recorded at the height of her career, which took place during her early years at Atlantic Records, the album offers irrefutable proof of Franklin’s prodigious contributions to American culture.

While at her first label, Columbia Records, Franklin was allowed only to sing, and as a result, never scored a major hit. Not until moving to Atlantic did she begin to arrange her own songs, and accompany herself on the piano. Franklin’s first studio session for Atlantic was to record “I Never Loved a Man (The Way That I Love You).”

“It just wasn't coming off,” Franklin told NPR. “And finally someone said, ‘Aretha, why don't you sit down and play?’ And I did, and it just happened. It all just happened. We arrived, and we arrived very quickly.” Quickly indeed, between 1967 and 1968 Franklin scored ten Top 10 hits. “I Never Loved a Man” was credited, by music critic Peter Guralnick, as an uniquely monumental moment in American music. This was the energy in the room there at Berns Salonger on May 2nd, 1968.

Franklin's gospel idiom is on full display on Berns Salonger, as are her most famous secular soul recordings: “Natural Woman”, “I Never Loved a Man,” “Dr. Feelgood.” What has always struck me about Aretha's signature songs is their palpable sexuality. Something she was often coy about in interviews. It’s hard to believe she was naive to her own sensuality, or rather, that of her recordings. These are devout songs, all of them, but the object of their devotion is very often a man and his prowess. Very few singers can muster such carnality — can invoke a hallelujah not for God but for his masculine image to be found in dark, hot rooms. The song, also my favorite, which most displays that tension between the holy and the horny, is “Dr. Feelgood.” The best rendition of which appears on this record. The third song in the set, and the first to be introduced by Aretha’s banter, sees her, for the first time during the show, sit down at the piano. She says, “In a moment I will take the seat of the young man you’ve heard accompany me so ably.” She takes Gary’s seat, lets out a fake cough, complains of laryngitis, and says “I’d like to talk to you right now about that Dr. who visited me…” Then begins the piano: moody, bluesy, petulant. Then begins the voice: moody, bluesy, petulant. “I don’t want nobody always sittin’ ‘round me. And. My. Man.” That is a hungry voice, a voice unwilling to share, a voice demanding her full portion of man. This is Aretha the singer and the pianist at her absolute best; taking the idiom of her church into more immediate, more exciting domains; sanctifying the daily goings-on between bodies.

It really doesn’t matter what Aretha sings about. Much ado has been made about the feminist legacy of “Respect,” her unexpected mastery of the tenor aria “Nessun Dorma,” and her relationship to the black church and the civil rights movement. Womanhood, virtuosity, faith, and blackness were all integral to Aretha the person, and the artist. But the crucial element was always the voice. Not the place or time, the lyric, language, or the theme. What made her great was that whenever she sang about something it became dignified, elevated, baptized. Her voice was an instrument of consecration, and whatever enjoyed its attention was better off as a result.

The experience of listening to Berns Salonger is one of rapture, and of a directional paradox. On one hand, she herself ascends, perilously, grasping for whatever piece of sky within her reach. On the other hand, is the descent, equally perilous; the avalanche falling on our heads. That has always been my experience of encountering genius: being bombarded, battered, besieged, until I submit totally to the phenomenon. Genius makes the critic’s job difficult. There isn’t much to say, even less to sift or parce; you cannot draw lines in moving sand. We are reduced to eyewitnesses, testifiers. Doomed to paint, always inadequately, some impression of what happened then and there, what is still happening here and now. Some voices liberate us from our myopic view of time and space. They perpetuate themselves — as does the universe — byway of infinitely many reactions, forever rending the vibrational fabric. Aretha’s is one of those voices. In her sound, accent, disposition, is the convergence and divergence of many ancestors and of all progeny. Past and future lose their meaning. They are too small for Aretha. Perhaps that is why I’ve never truly grieved her death, because she feels no more lost to me now than she felt possessed by me then. She has always been an aberration, an encompassing presence. She had always about her the shimmer of a ghost, and a holy one.